“Yes!” Maestro Long Yu has spoken in Chinese for much of his announcement, but this is a word I recognize. A fleet of cooks in crisp chef's whites and towering toque blanches have appeared before a bustling dining room. Each chef holds a tray displaying the gourmet crown jewels of Beijing: Peking ducks. Yu heralded their arrival to Beijing Music Festival colleagues, including the Hong Kong Philharmonic and its conductor, a very amused-looking Jaap van Zweden, who is within arm’s reach of the glistening amber birds. Suddenly, the chefs snap into action. They bellow what sounds like a culinary war cry and proceed to carve in unison, slicing off breast meat as if it were soft butter.

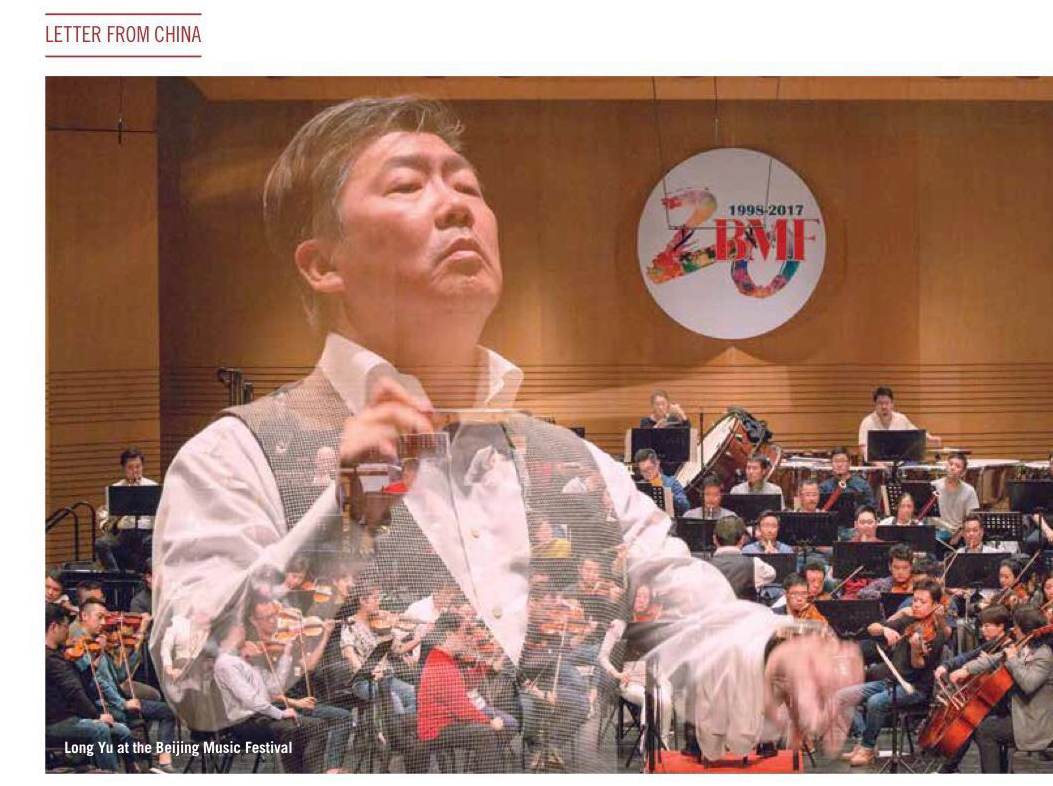

Witnessing these meat mages at work wasn’t what brought me to China. Yet the spectacle seemed to embody much of the enthusiasm of the 22-day festival last October. With bold programming and packed-in audiences, its 20th-anniversary season was an earnest, unabashed celebration of classical music—something all the more fascinating considering it was, for some time, banned here altogether. With its inception in 1998, BMF and Yu have been linchpins for the art, and a kind of barometer for the groundswell. Yu told me that over the past two decades, more than 60 orchestras formed—a rate of addition celebrated by this festival. As if mustering China’s musical firepower, nine orchestras played back to back in a "marathon” over one day.

Programs also included operas, traditional music (both European and Chinese), symphonies, and children's concerts, though I saw plenty of children at other performances. After van Zweden and the Hong Kong Philharmonic delivered a lushly textured performance of Bruckner’s Symphony No. 8 in C minor, I witnessed a young girl pose, peace sign and all, before a poster of the maestro.

Business seemed to reign in global Beijing, where skyscrapers sport English lettering alongside Chinese characters. I spoke with several locals who described relentless work weeks; they chuckled at the notion of a long vacation. Yu referenced this immediately. "The young people, how they grow up...” he said. “I don’t want them to stick with doing [only] business. I’m hoping we can share more culture, music, and beauty of life.”

Perhaps this is why BMF feels much like a global cultural tour. There was traditional Welsh music, Silent Opera London, and a concert of Russian choral works from the past century. Conductor Paavo Jarvi and the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen brought a hulking display of Beethoven to Beijing; they performed the city’s first-ever complete symphonic cycle. It’s no surprise they've tackled it several times—their playing was electric and nimble, a gratifying dive. Violinist Frank Peter Zimmermann and his son Serge Zimmermann joined forces for the opening concert, which included the Beethoven violin concerto and Bach Double concerto.

The Salzburg Easter Festival collaborated with BMF to reach through time to quasi- resurrect a 1967 Salzburg production of Wagner’s Die Walkiire by Herbert von Karajan. From the pit, Jaap van Zweden and the Hong Kong Philharmonic whipped up the enchanting, familiar score against epic, transporting sets that included cosmic backdrops and a gargantuan tree.

There was also a strong theme of union, and a focused lens on China itself. “The festival is obviously like a platform to share with everybody. It’s not only a showcase,” Yu said. “We’re not interested in only [being] a stage for the elite. Everyone has the right to be here.” Yu tore into a candy bar in his dressing room of Beijing’s Poly Center. After hours of rehearsal, he sat for what appeared to be the first time that morning. “I think with music, you share the feeling with all the other people together,” he added. “Most of the problems today in the world are [from] misunderstanding."

All these concepts converged at the closing gala. Composer Qigang Chen was commissioned by the festival to write a new violin concerto. Maxim Vengerov, in his third BMF performance, gave the world premiere at a concert that also included a rural farmers’ choir and next-generation

pianist Serena Wang. Chen was a suitable agent for this foreign exchange. He’s Shanghai born,but was Olivier Messiaen's final student and now resides in France. His concerto reflects on the mercurial link between joy and suffering. Speaking via translator, he said the work felt“like a new baby. With a new-born, even the mother doesn’t know all the characteristics.” It has a French title but mirrors the Chinese concept of yin and yang, merging elements of East and West. Vengerov shared that learning it was a “spiritual” experience.

Vengerov began with a few fragile bow strokes barely louder than whispers. The energy quickly surged with more volatility, mounting to a stunning virtuosic part that embraced ricochet staccato, left-hand pizzicato, tenuous harmonics, and quick tumbling runs. His playing was carefully shaded, at times nuanced by quavering vibrato and at others whirling in a staggering yet pleasing contrast to the orchestra, which drew from a succulent palette that evoked a hypnotizing Chinese landscape. It was a crackling cap to an eclectic festival season.

By Cristina Schreil